John Schulz works in Saint Paul, Minnesota and makes work at the Highpoint Center for Printmaking in Minneapolis.

John repurposes commonplace, cast off, and outdated printed matter using cut-up methods and chance operations, believing that even the most banal images are deeply rooted in the fabric of our day–to–day experience and collective psyche. He is currently investigating mid-century public domain Science Fiction, Crime, and Romance comics, fragmenting their images and text, liberating them from their original narratives and recombining them to create new, unexpected visual forms and readings.

Although John has never taught a comics class per se, he regularly uses examples of comic art when teaching woodcut:

“Using comics is a great way to get students’ attention, talk about building compositions in black and white, work with line and form, and create visual flow and tension. The D.C. Comics Guide to Inking Comics by Klaus Janson and Drawing Words & Writing Pictures by Jessica Able and Matt Madden have excellent examples and illustrations on all of this. Lynda Barry’s books Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor and Making Comics have been invaluable in coming up with experimental methods for generating images and getting a class moving on day one.

I show work by artists that relate to comics, such as the early “wordless novels” of Frans Masereel (Passionate Journey) and Lynd Ward (God’s Man), as well as work by Felix Vallotton, Kathe Kollowitz, James Ensor, H.C. Westermann, Jess Collins, and Ray Yoshida among others. There are also correspondences between comics and popular culture and the production of Ukiyo-e prints in 17th – 19th century Japan, and I use comics (and manga) to introduce and investigate that material as well.”

More images of John’s work can be viewed at https://www.johnschulzartist.com/ or on Instagram @jschulzdrawprint.

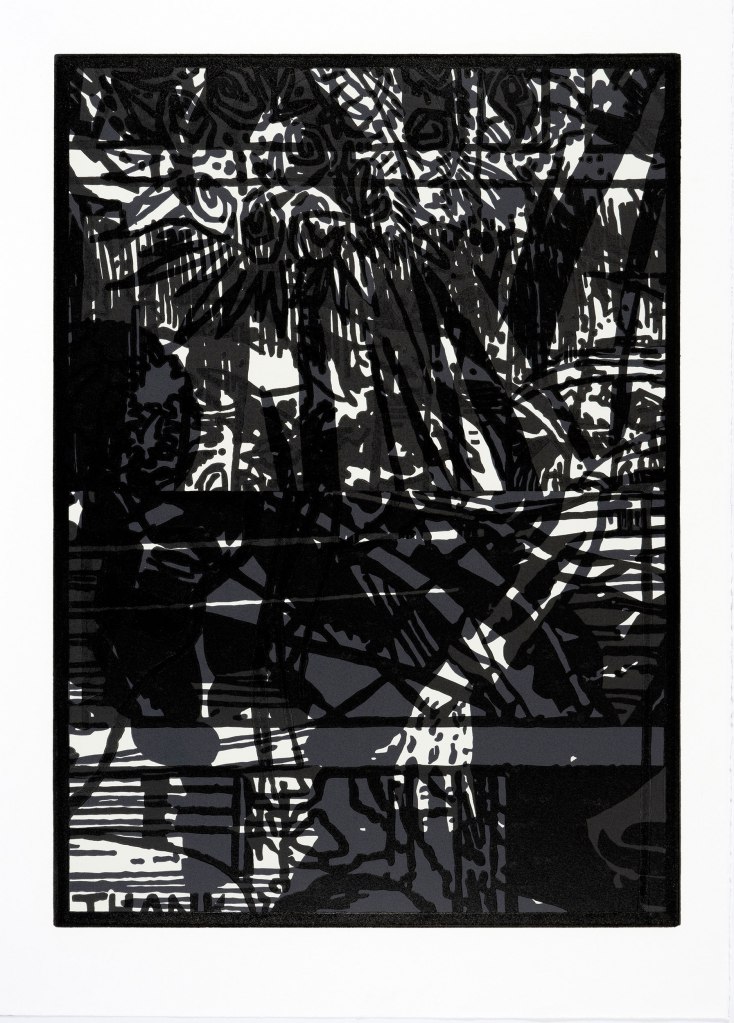

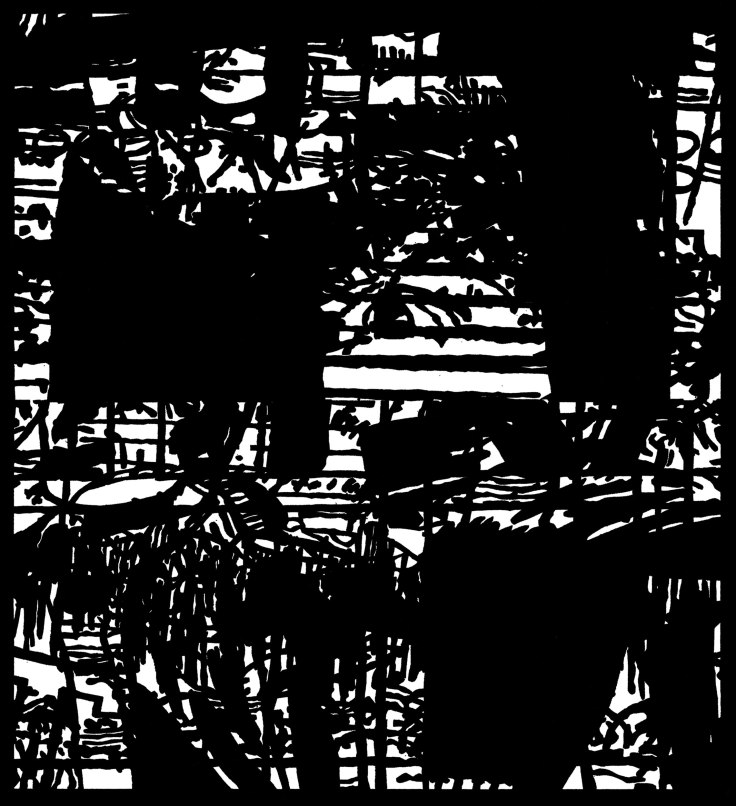

Color woodcut on Rives BFK

28″x20″

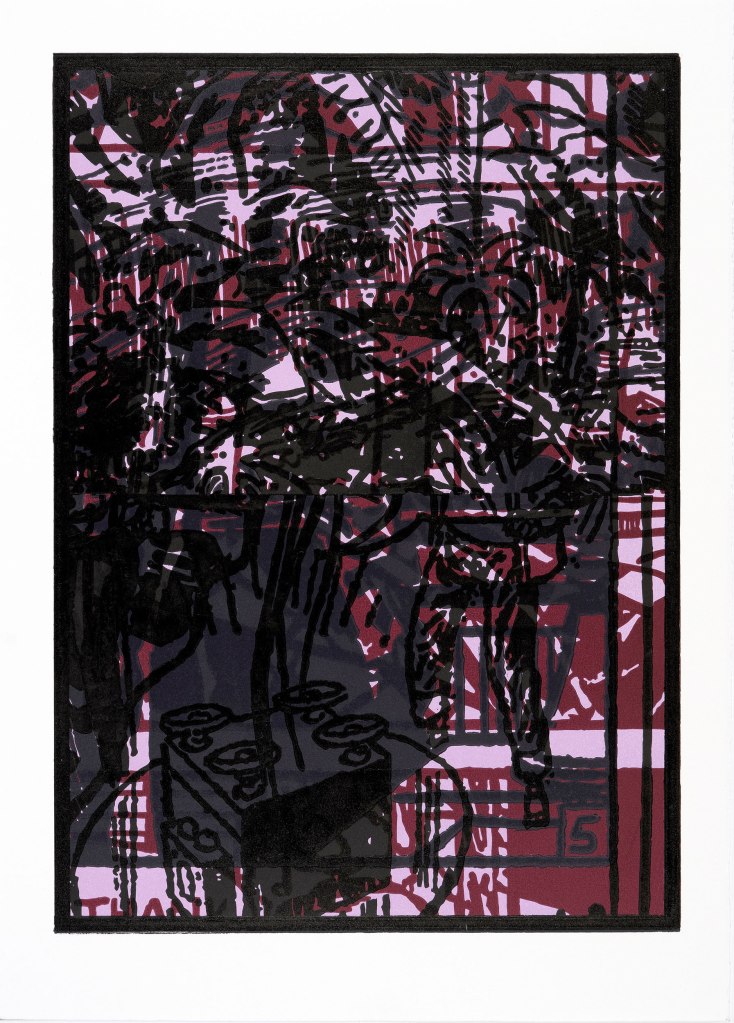

Color woodcut on Rives BFK

28″x20″

Did you grow up reading comics, and did you have any moments in your life when you stopped reading comics??

I remember looking at comics before I could read, and learning to read via the comics section in the daily paper and the Sunday Funnies (Dick Tracy, Little Orphan Annie, L’il Abner, Pogo, Peanuts). I would say the funny papers were one of my most important, fundamental visual experiences. Then comic books started finding their way into the house (Carl Barks’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, Floyd Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse, Hank Ketcham’s Dennis the Menace, Mort Walker’s Beetle Bailey) along with illustrated books like Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon and Dr. Suess’ The Five Hundred Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins.

As a kid, my parents were cautious about what they’d let me read, but then one day I discovered my uncles’ stash of Batman and Superman comics in a back closet at my grandmother’s house, which sort of lent reading comics a conspiratorial air that has stayed with me to this day.

We didn’t have TV when I was very young, so I’d go to friends’ houses to watch cartoons and they had other kinds of comic books. I distinctly remember reading my first Marvel comic, Fantastic Four #5, with the first appearance of Dr. Doom (July 1962), and realizing that there was a whole other thing going on aside from the hermetic Disney and D.C. universes I had known. Then, when I found a stash of my dad’s paperback reprints of the original EC Mad and Charles Addams’ Addams Family in a dusty box of old books (also in a back closet), my world changed again.

I’ve never stopped reading comics, although there have been dry spells mostly due to lack of funds. Lately, I’ve been reading the IDW complete reprints of Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie and Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese, everything I can get my hands on by Jaques Tardi (The Extraordinary Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec), and collecting stuff like back issues of Jack Kirby’s Machine Man and The Demon, Sam Glanzman’s Kona, Monarch of Monster Isle, Charles Biro’s Crime Does Not Pay, and Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s Young Romance comics from the 1940s – 50s.

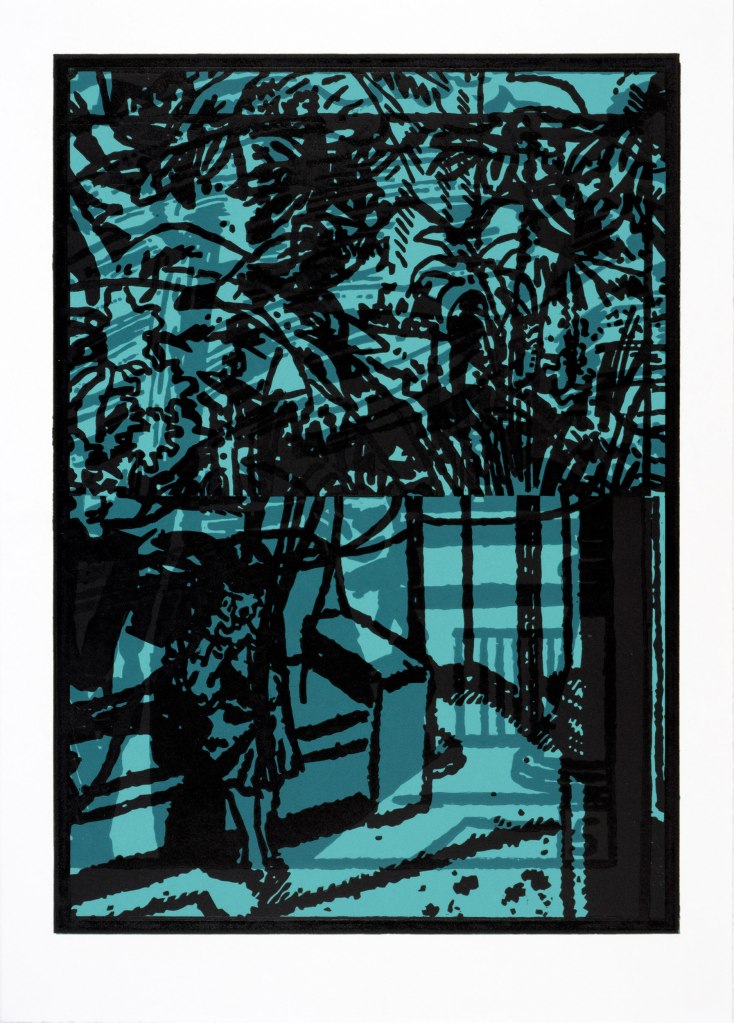

Color woodcut on Rives BFK

28″x20″

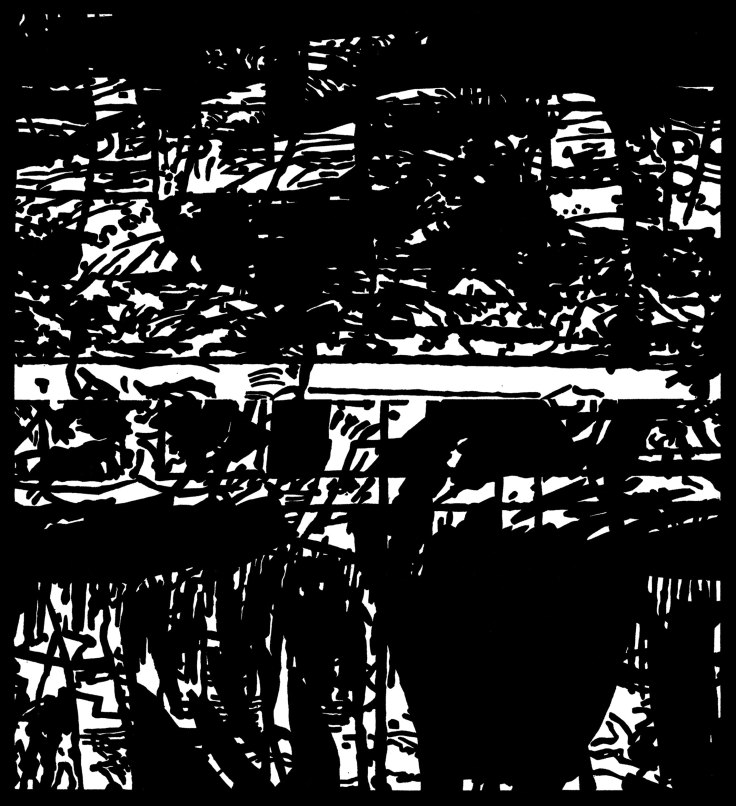

Color woodcut on Rives BFK

28″x20″

Have you ever felt embarrassed or ashamed about reading comics?

No. It’s an art form. I’ve known that instinctively from the get–go. Will Eisner finally gave a name to it in his book Comics and Sequential Art in 1985…

Color woodcut on Rives BFK

28″x20″

Color woodcut on Rives BFK

28″x20″

Do you have a favorite comic shop that you visit? Where is it? What makes it so great?

These are all incredible shops in their own ways, mostly having to do with their owners’ unique interests, the passions of their staff, and the breadth and depth of their inventory:

Boston/Cambridge, MA: The Million Year Picnic, Hub Comics, Comicopia

Antwerp, BE: Mekanik Strip

Minneapolis, MN: Dreamhaven Books, Nostalgia Zone

and…

Superior, WI: Globe News

Globe News is where it all started for me, from Uncle Scrooge to The Fantastic Four to Rolling Stone, The National Lampoon and beyond (e.g., the comic books were somehow in close proximity to what are now referred to as “mid–20th century men’s magazines”). Globe also had a huge selection of magazines and paperbacks ranging from trashy pulp noir, sci–fi, and romance to popular mainstream novels like Joseph Heller’s Catch–22, Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001, and John Updike’s Rabbit Run. A great newsstand, not a bookstore, that also served as proof that comics can be a gateway drug to literature.

Color woodcut on Rives BFK

28″x20″

How do comics inspire or inform the work you make?

I am extremely interested in the work of the French comix group OuBaPo (Workshop for Potential Comics) and their use of constraints (rules of sequence and format) in manipulating comics’ formal elements. Some examples of OuLiPolian constraints are Reduction, a book or comic summarized in very few panels; Reversibility, a comic that can be read back to front; and Iconic Alliteration, the same drawing reproduced throughout the whole comic with only the words changing. One classic example is Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story: Exercises in Style, illustrating 99 different approaches to telling the same story (man goes to fridge and forgets why) in series of a one–page comics. Much of Art Spiegelman’s early work, such as Nervous Rex: The Malpractice Suite and Ace Hole, Midget Detective also work to deconstruct the medium.

I am influenced by the cut-up methods and collaborative work of William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin (The Third Mind), which involves taking a finished and fully linear text, physically cutting it into pieces and rearranging the pieces to form new narratives. The method also allows for recombining multiple texts and writings of different authors. I am also interested in the aleatory methods used by Samuel Beckett, as in his short story Lessness, which he wrote by drawing a set of sixty pre-written sentences out of a hat, twice.

And I am a big fan of Five Card Nancy, the “Dadaist card game” invented by Scott McCloud, author of Understanding Comics, that plays with the potential fluidity of sequencing and narrative by cutting up and reshuffling individual panels from Ernie Bushmiller’s long-running Nancy comic strip to make new stories.

My current investigations involve working with public domain Crime, Romance, and Horror/Fantasy/Science Fiction comics from the 1940s – 60s. This in part a response to the U. S. Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, established in 1953, which was tied to perceived excesses in Crime and Horror comics of the time, led by Dr. Fredrick Wertham‘s popular and sensational book Seduction of the Innocent. In the end, this resulted in the establishment of the Comics Code Authority, self-censorship, and a general dumbing-down of the medium. Romance comics were also attacked by Dr. Wertham for their over-romanticizing, social insincerity, titillation, and cheapness. Following through with Burroughs’ cut-up method to bring these three genres together seemed to be a good idea.

Comic books and strips were originally made for the widest possible distribution and are now entrenched as an essential part of popular culture. I am drawn to woodcut as a medium because a part of its history as a broadly, based “low” art form makes for a logical conceptual connection to comics in the context of my work. I am drawn to comic artists who make dynamic use of fluid brushwork and powerful lights and darks, in the manner of Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates), Chester Gould (Dick Tracy), and Hugo Pratt (Corto Maltese). I find this style translates well in terms of mark-making when I re-draw the images and build them up on the block in ink before cutting; I have always felt a close relationship between brushwork and using carving tools.

Color woodcut on Rives BFK

22″x20″

Color woodcut on Rives BFK

22″x20″

How long have you been making work that references comics?

I have been working directly with images from comics for around ten years. Prior to that, I had a long history of working with cast-off printed matter, images from dated government intelligence tests, instruction booklets, first aid manuals, old 19th & early 20th century schoolbooks, used coloring books, giveaway cookbooks, 1940s Montgomery Ward catalogues, and whatever other detritus came my way. But I consciously avoided using comics because of their specific reference to a particular medium, and not wanting to bother with any sort of potential copyright issues that would automatically come to dominate the work.

Basically, I was generating unexpected combinations of found images and text using random procedures such as blind draws, and later, keying sets of images to the I Ching. Visually, these were tied to Emblemata and Emblem Books, allegorical prints with accompanying explanatory text (typically morals or poems) popular in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries. These are often seen as precursors to comics in their interweaving of text and image, but they were intended more as an amusement for the intelligentsia than popular prints intended for the general population.

At one point, I started physically cutting apart my collection of source material, making collages by re-ordering and tossing together fragments of images, and making books to play with page transitions and sequencing. My initial impulse was to get away from working primarily in Photoshop and get back to a starting point that was more spontaneous and physically connected. This evolved into a mail art collaboration with a like-minded former student who had just moved back to Philadelphia. Comic book clippings started showing up as a regular part of what he sent along, and as the project was essentially a game, with the results never really intended to be seen by anyone, there was no reason NOT to throw comics into the mix along with everything else.

I found that the clippings I was getting were decontextualized to the point that their sources were no longer identifiable (e.g., no super-heroes) recalling Ray Yoshida’s comic collages of the late 1960s. These also suggested Jess Collins’ Tricky Cad, a surrealistic reconstruction of Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy that echoes the collages of Max Ernst. Gradually, since I had now had these comic bits in my cut-up box, they started working their way into images I was developing for woodcuts.

I then started working with comic books themselves, cutting up scanned pages from different genres into horizontal and vertical strips, re-weaving them together, and then cutting them apart to generate new sets of images from the unanticipated juxtapositions. These were then re-scanned, cleaned up, and converted to black and white before being transferred to woodblocks, and back into print media from which they came. The resulting images can be rearranged into sequences or grids that imply new narratives. Working in Photoshop also lets me work with transparent layers, stack images on top of one another, and then overlap them in the prints to further mask their specific identities.

In the end, I want the original content to be visually present but buried as part of the enigma of a larger whole, offering a glimpse of something familiar beneath the surface, as in Francis Picabia’s Transparencies (1927 – 1933), and Willem deKooning’s paintings Attic (1949) and Excavation (1950).

“Arthur Schopenhauer wrote that dreaming and wakefulness are the pages of a single book, and that to read them in order is to live, and that to leaf through them at random, to dream.

– from “When Fiction Lives in Fiction,” Jorge Luis Borges, 1939

I am currently working on integrating obscure American Funny Animal Comics from the 1940s – 1950s into the mix, as they have been ever-present alongside the other genres I have been referencing and have deep roots going back to the beginnings of storytelling and images-making across world cultures.

Besides, what could possibly be more frightening than an anthropomorphic six-foot talking pig walking upright wearing a suit-coat but no pants?

Archival inkjet

66″x60″

Archival inkjet

66″x60″