Deb Sokolow works from a tiny rooftop room on top of the building where she lives in Chicago, Illinois. She also has a studio in an old building in an industrial area west of the West Loop.

Deb Sokolow makes drawings and books which speculate with humor and criticality on a number of subjects including architecture, politics, organizational structures and the human psyche. Sokolow’s most recent text-driven, maquette-like drawings visualize ideas in which architecture, design, psychology and social engineering overlap.

Deb teaches a course in the Department of Art Theory and Practice at Northwestern University called Drawing Humor. Which is adjacent to and sometimes overlaps with comics, where students spend quite a bit of time in the course talking about the relationship of image to text. Also, every week students brainstorm possible captions together for The New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest.

Images of Deb’s of work can be viewed at www.debsokolow.com, on Instagram @debsokolow and at www.westernexhibitions.com

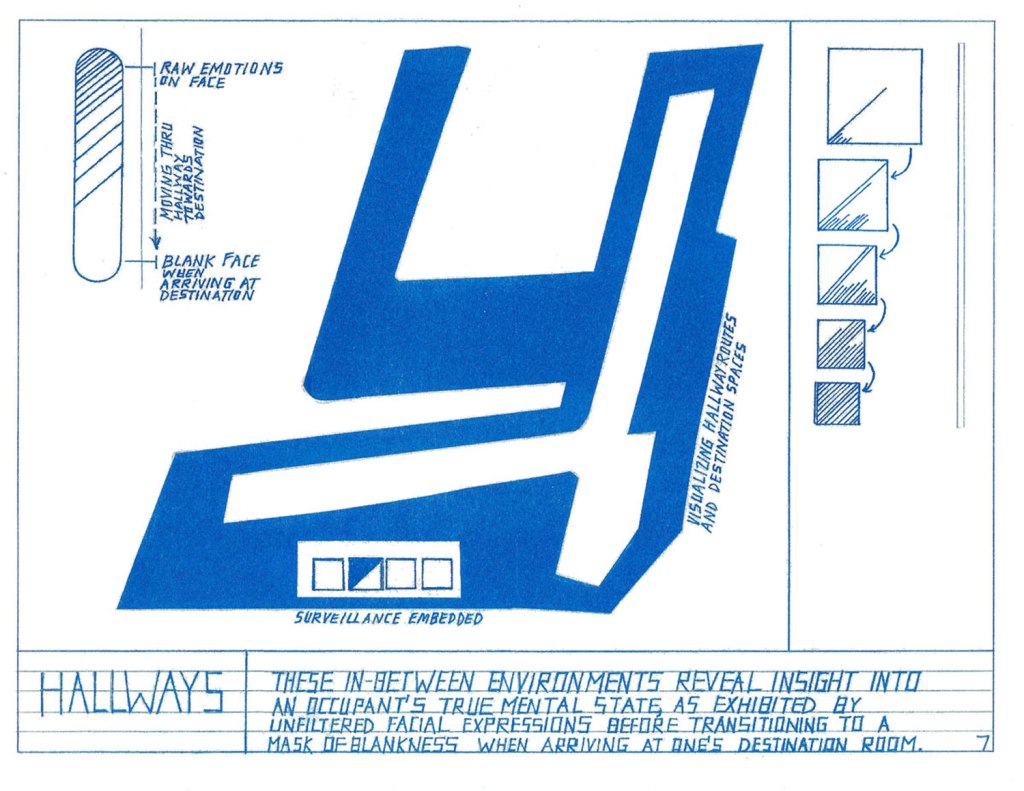

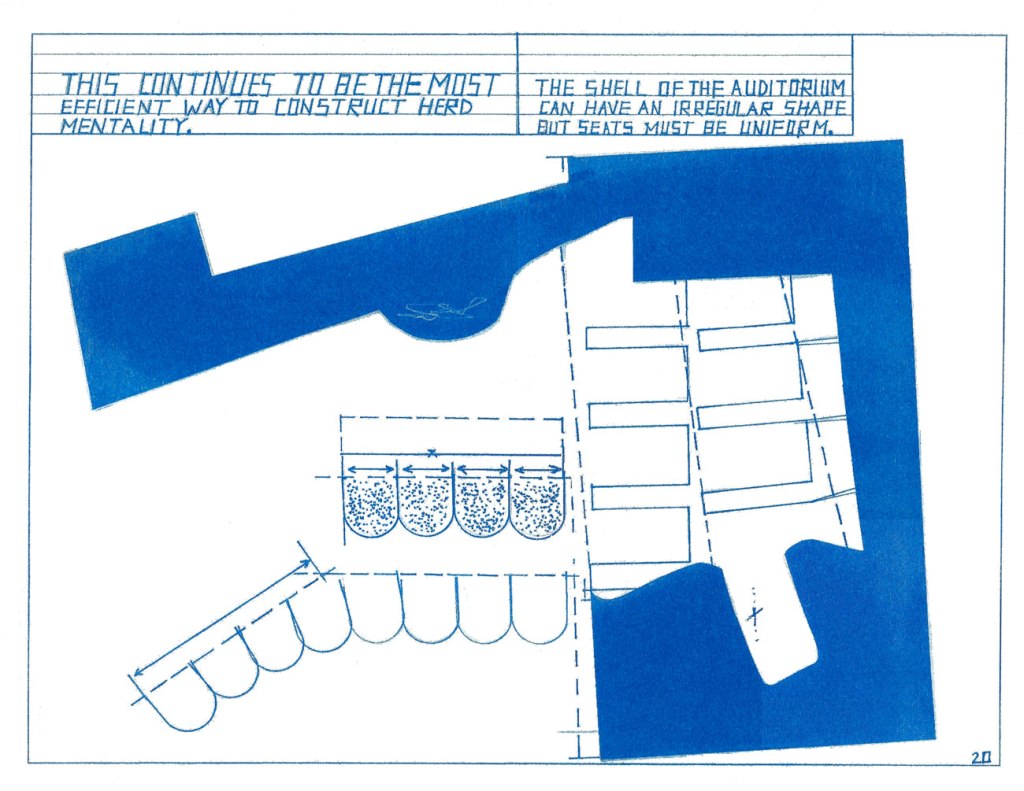

Risograph, artist book, 8 1/2″x11“

Risograph, artist book, 8 1/2″x11“

Did you grow up reading comics, and did you have any moments in your life when you stopped reading comics??

I did not have a lot of exposure to comics as a kid, other than following various comic strips like Cathy and Sylvia and Doonesbury in the newspaper, being gifted a Far Side book of comics, and buying a few Archie comics with birthday money. I grew up in Davis, California, a liberal college town near Sacramento, and there were some well-known artists, such as Robert Arneson, Roy De Forest and William T. Wiley, teaching at the university that were part of the funk art movement and made work that felt comic-adjacent and focused on things that eventually turned up in my own work like humor, a playful use of color and the autobiographical. Elements which were not at all in sync with what the New York art world was into then. Those artists at UC Davis shared similar sensibilities in a similar time frame with Chicago Imagists like Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson and Suellen Rocca, who I wouldn’t discover until I moved to Chicago, but as a kid I could see the legacy of Arneson and the work of his students in the various public sculptures around town and in local artisan shops where there would always be a bunch of goofy mugs for sale.

I was a visual kid. I remember walking with my dad around the neighborhood and critiquing every single neighbor’s front yard. Whenever I visit my home town now, I still do this. (Too many wood chips! Excellent ceramic planters!) I also remember paying close attention to the design of things: toys, product packaging, and the illustrations on greeting cards. When I was a teenager I worked in the children’s section of the local library and spent quite a bit of time shelving books, looking at their covers and thumbing through pages of illustrations. I loved to read fiction and spending so much time at the library helped me form that habit. I had taken a few art classes by that point and was making (unintentionally awkward) comic-like satirical illustrations to accompany opinion pieces penned by other students for the high school newspaper. I loved the art classes I had been in, but they weren’t formal. Maybe that is indicative of junior high and high school art programs in general or maybe it was more about it being California in the late 1980’s/early 1990’s. We weren’t taught any technical info on how to make art, but were encouraged to find our voices. So I didn’t really know how to draw at that point, and I had trouble with composition and line weight, but my poorly executed drawings did have a “voice.” If I’d had more exposure to comics and had forced myself to learn some basic drawing skills at an earlier age, I might not have struggled so much with making those newspaper illustrations.

At the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, I majored in graphic design, thinking this was a more practical option than fine art, but then went on to grad school for an MFA at the School of the Art Institute. I continued to draw, still struggled with it, but I kept at it. I was drawing floorplans and cartoon-like renderings of buildings, objects and people and focusing on the autobiographical, mixing fact with fiction, and working with different types of humor (satire, the mundane, self-deprecation). Post-grad school, the work continued to evolve. Today, 20 years later, the drawings are semi-abstract schematics and shapes paired with texts, but the floorplans, other references to the built environment and various forms of humor continue to play an important role in it.

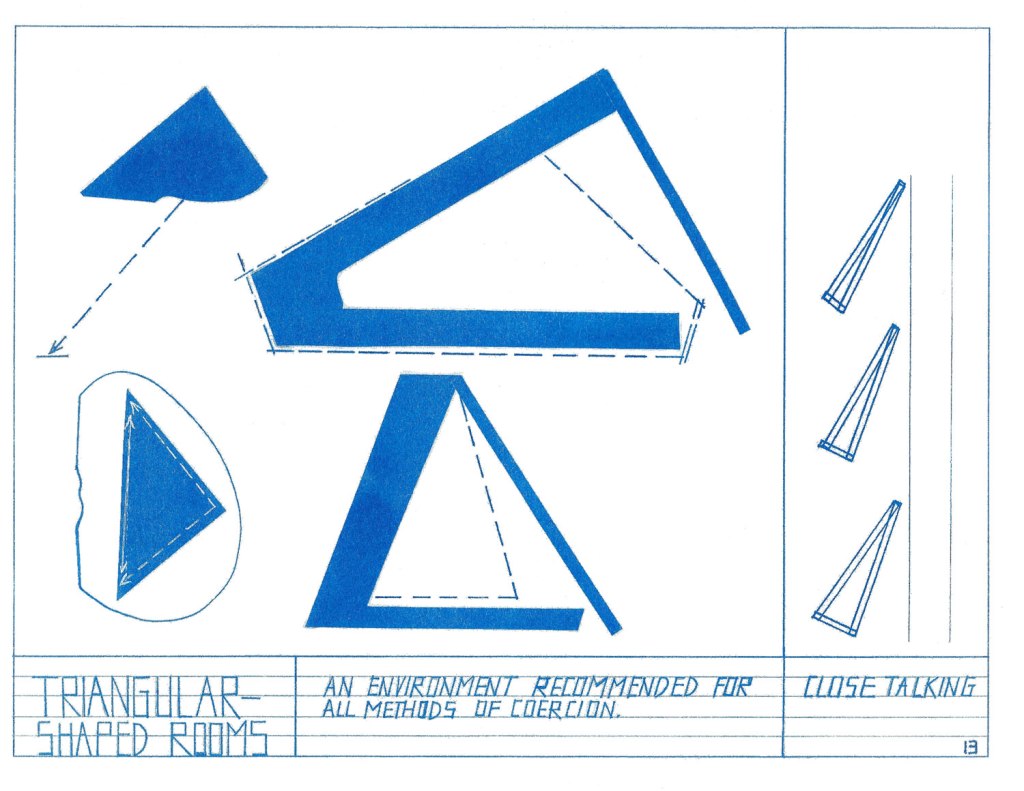

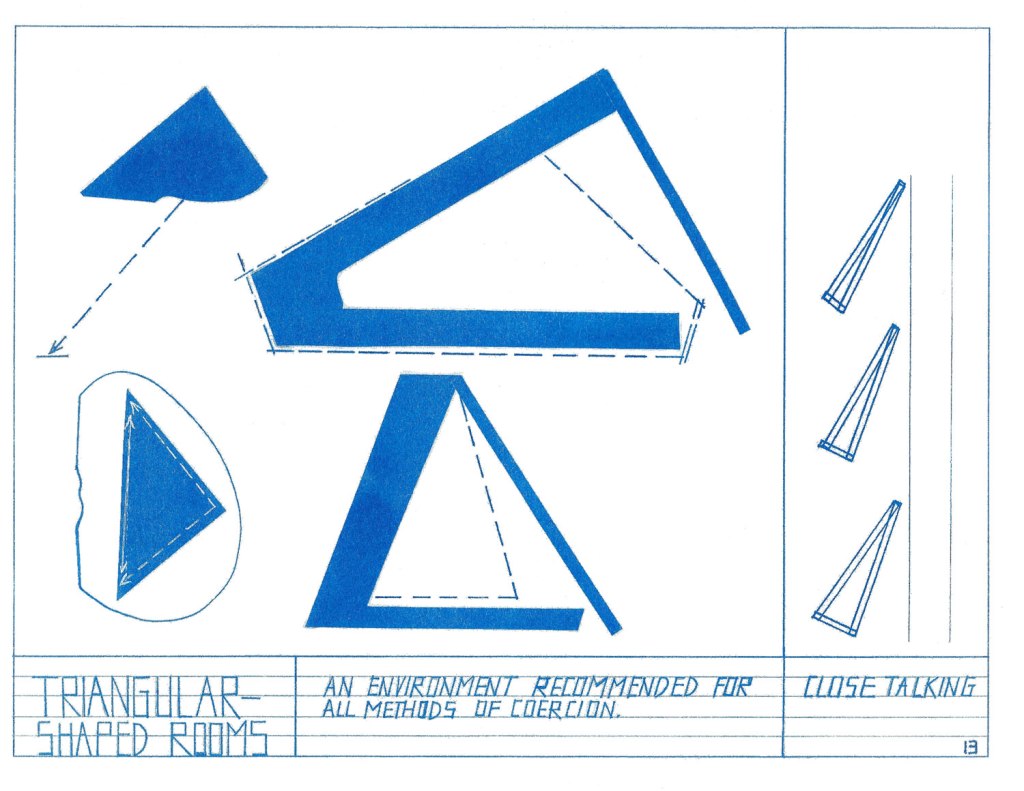

Risograph, artist book, 8 1/2″x11“

Risograph, artist book, 8 1/2″x11“

Have you ever felt embarrassed or ashamed about reading comics?

Never! My only embarrassment comes from not reading enough comics and not being knowledgeable enough about the genre. There’s so much cool stuff out there, it feels pretty overwhelming, and I never have enough time to do a deep dive into it.

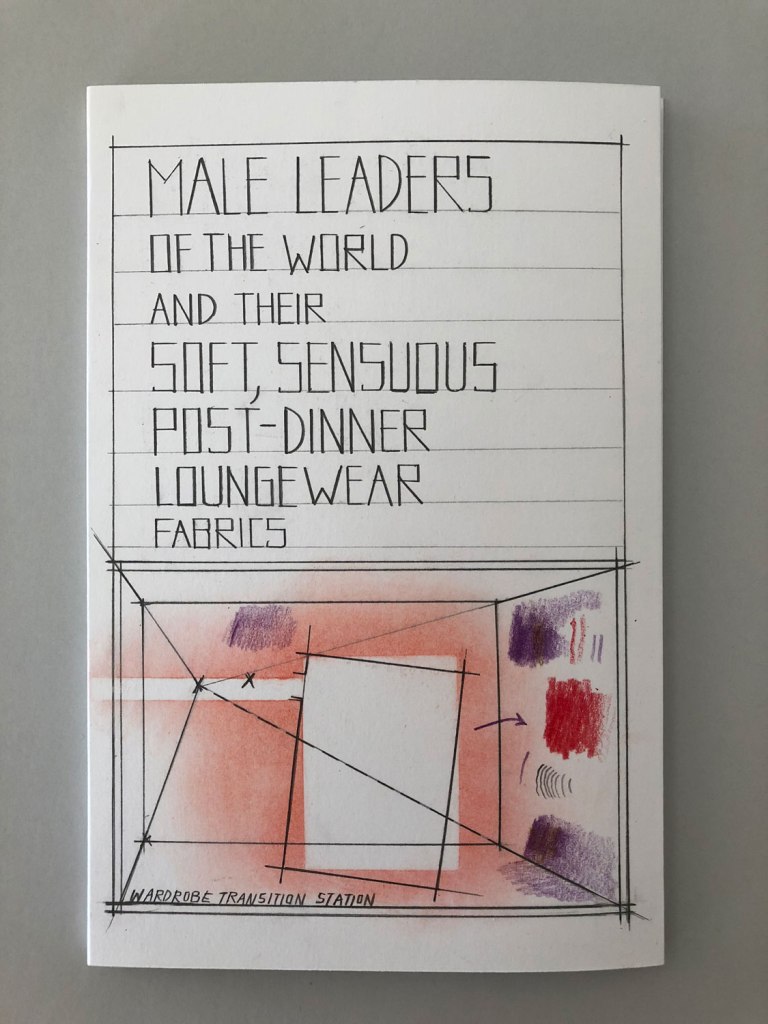

Artist book, cover: graphite, crayon, colored pencil;

text block: archival inkjet print on archival paper

Accordion fold: 9″x6″x1″ (closed), 9″x44″ (open)

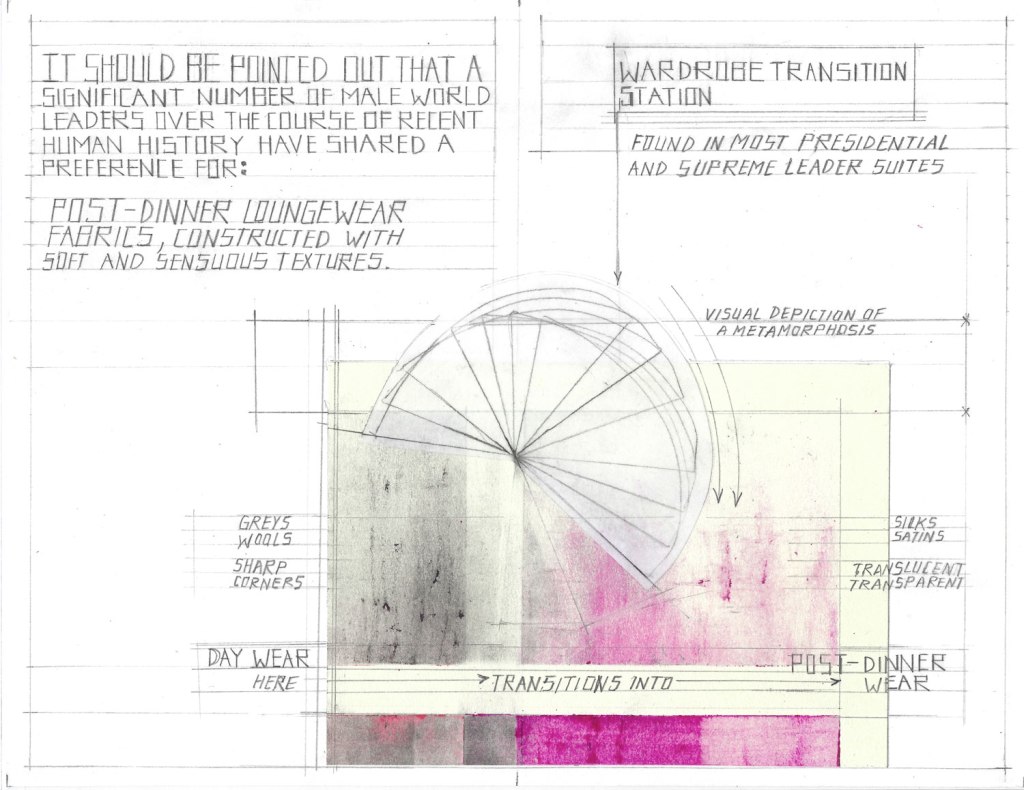

Artist book, cover: graphite, crayon, colored pencil;

text block: archival inkjet print on archival paper

Accordion fold: 9″x6″x1″ (closed), 9″x44″ (open)

How do comics inspire or inform the work you make?

Graphic novels are what I gravitate to the most. Both Emil Ferris’ My Favorite Thing is Monsters and Viken Berberian’s totally sly, smart, engrossing graphic novel, The Structure is Rotten, Comrade, gorgeously illustrated by Yann Kebbi are two of my absolute favorites. Ferris delves deep into issues of class, race, gender, cancer, coming out, coming of age, drawing, looking at art, being a monster, loving monsters, sleuthing, and Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood in the 1960s. And Berberian focuses on architecture, class, Yerevan and the search for the Golden Mean. Both inspire me to become a better writer and to really think about all the possibilities for how my writing and drawings can operate together, such as when the two intentionally don’t quite match up, or when they purposefully match up too well in an over-redundant and ridiculous way. Often, something is revealed in the visuals that is not mentioned in the text, and vice versa.

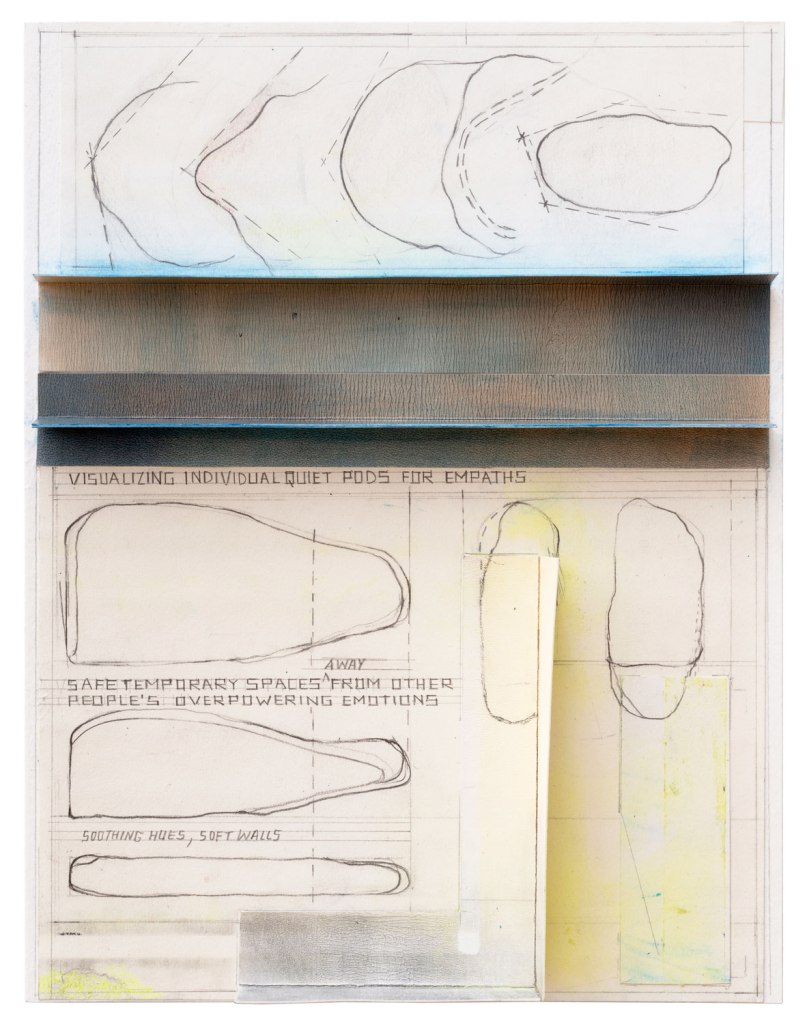

Graphite, crayon, colored pencil, pastel and

collage on paper, 11″x8 1/2″x1″

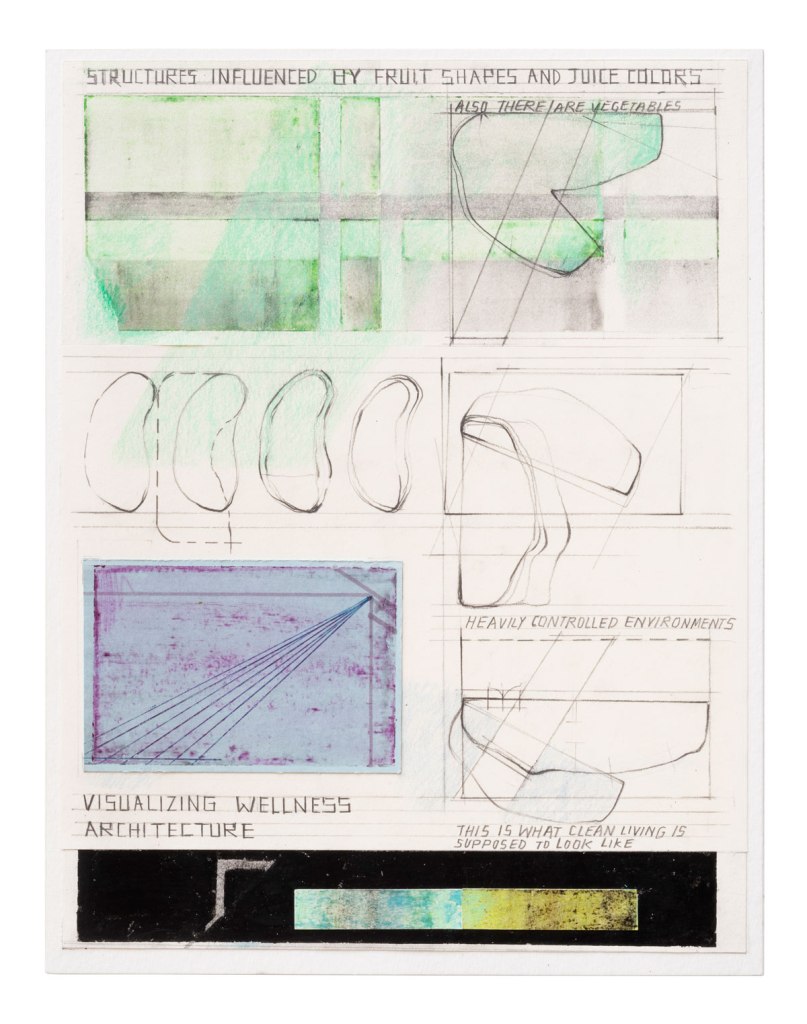

Graphite, crayon, colored pencil, pastel and

collage on paper , 11″x8 1/2″

Have you ever been afraid or worried about making artwork that references comics?

In grad school I had two encounters, one with an art historian and one with a painting professor. Both expressed condescension towards what I was doing- combining drawing with text and working in a narrative form. One said he didn’t like to read art. The other one pointed out that looking at my work felt like doing homework, and he didn’t want to do homework. These criticisms are what drive me to try and make work that is interesting to an audience and to be a better editor of my text. If someone spends less than 1 minute looking at a gargantuan drawing I’ve made, I know that I’ve failed and the professors have won. There have been times when I’ve put a piece out there in the world and have lost this contest.

Graphite, crayon, colored pencil, pastel, ink and

collage on Arches paper, 22″x30″x1″

Graphite, crayon, colored pencil, pastel, ink and

collage on Arches paper, 22″x30″x1″